Please click each section heading for the full text of that section.

Indicators and Data Points

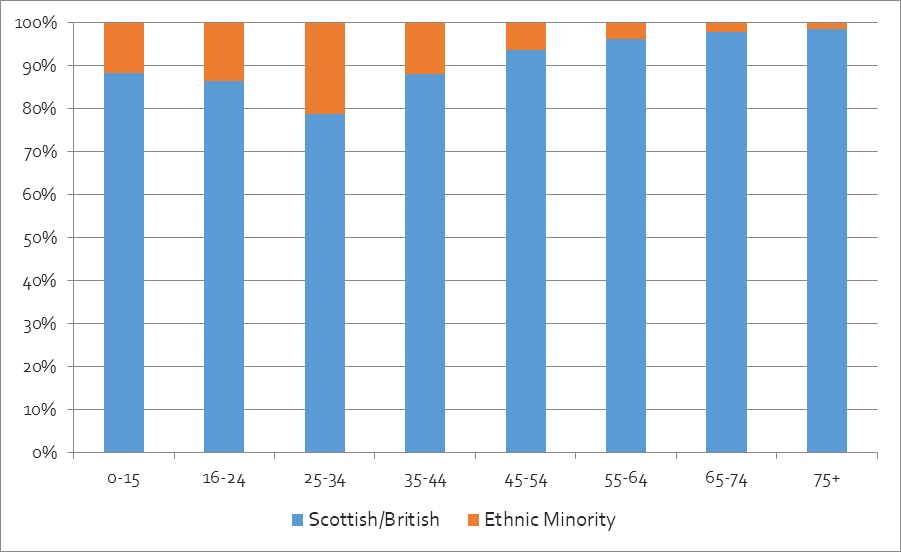

Age Distribution

For the Grampian region in the 2011 Census, the largest age group for both ‘non-white’ and European ethnic minorities was 25-34, and there were very few ethnic minority people of retirement age or older. This is significant for health, as younger people tend to be healthier.

Grampian Age Distribution, 2011

Data Source: 2011: Scotland’s Census, Table DC2101SC.

Disability & Long-Term Health Conditions

One-fifth (20%) of people in Scotland have a disability or a long-term health condition affecting their day-to-day activities. For ‘non-white’ ethnic minorities, the figure is 9% – the data is not available by country of birth or other characteristics, so European ethnic minorities are not accounted for.

In Grampian, 16% of the population has a disability or long-term health condition, including only 4% of people from ‘non-white’ ethnic backgrounds.

Data Source: 2011: Scotland’s Census, Table LC3205SC.

General Health

As shown below, the general health of ‘non-white’ ethnic minorities tends to be better than for ‘white’ people in Grampian and across Scotland as a whole. This likely relates to different age profiles, as shown above. Separate data was not available for ‘white’ ethnic minorities.

| Health Status | Ethnicity | Aberdeen City | Aberdeenshire | Moray | Grampian Average | Scotland Average |

| Good or Very Good | ‘White’ | 85% | 87% | 85% | 86% | 82% |

| Good or Very Good | ‘Non-White’ | 96% | 94% | 89% | 95% | 90% |

| Fair | Scottish/British | 11% | 10% | 11% | 11% | 12% |

| Fair | Ethnic Minority | 4% | 5% | 8% | 4% | 7% |

| Bad or Very Bad | Scottish/British | 4% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 6% |

| Bad or Very Bad | Ethnic Minority | 1% | 1% | 3% | 1% | 3% |

Data Source: 2011: Scotland’s Census, Table LC3206SC.

SIMD Health Indicator

In the SIMD Health indicator, only five of Scotland’s most deprived 10% of areas are in Grampian – 4 in Aberdeen City, 1 in Moray and none in Aberdeenshire. The proportion of Scottish/British in both the most and least deprived areas (in health terms) is similar – around 75%. However, the latter include a large proportion of people in the ‘other white’ category. Based on country of birth data for these data zones, most of these are from wealthier countries, including the USA, Canada, and EU pre-2001 countries (France, Germany, Italy, etc). On the other hand, ‘white’ ethnic minorities in more deprived areas tend to be from poorer countries in Eastern Europe.

Data Source: 2020: SIMD 2016 and 2020; Scotland’s Census , Tables LC2205SC and QS203SC.

Key Missing Data

The following data by ethnicity was not available for Local Authority areas or Health Board Areas: morbidity/mortality rates; immunisation/antenatal care; cervical and breast screening. More evidence is also needed on the impact of Covid-19 on ethnic minority communities in Grampian, and rates of disability within ethnic minority communities.

Qualitative Data from Relevant Local Research (2018-2021)

Grampian Health & Diversity Network Project

In a health community outreach project during the Covid-19 pandemic, a survey and series of discussions were held between March and July 2021, with 87 ethnic minority community members and health champions from 17 different nationalities/ethnicities. The main questions addressed access to health services, participation in engagement activities, and vaccine hesitancy.

Survey results showed that 17% of participants felt that accessing health and social care services was ‘Difficult’ or ‘Very difficult’. To improve access, participants suggested enhancing flexibility in service provision, including more flexibility in the hours the services are provided (including weekends), how appointments are scheduled and carried out (in-person, by phone, online or by video), and flexibility in the services offered in rural localities to avoid travelling long distances.

Overall, 9% of participants were dissatisfied with the health and social care services they received, and 17% did not feel well informed about these services. 21% felt their community does not get the support and information it needs to be a safe and healthy place, and 21% felt they cannot make a valuable contribution towards decisions in their local area regarding health and social care services. Around 80% of participants were either unaware or unsure of the opportunities available to participate in improving health and social care services, and they proposed providing more information and flexible ways to engage, which would increase participation.

Data Source: 2021: GREC. Link.

Community Planning Aberdeen, Population Needs Assessment (Health)

As a result of social isolation caused by lockdown, the health impacts of Covid-19, and the broader impact on the economy and society, mental health is an area of particular concern. Longitudinal analysis showed a rising number of people experiencing mental health problems, with some of the most significant impacts on groups who are already marginalised. These include ethnic minorities; young people; isolated older people; women; single parents; transgender people; and those with pre-existing or long-term mental or physical health conditions. People who are unemployed or in insecure employment were also more likely to suffer mental health problems.

The Population Needs Assessment cited ONS research from April and September 2021, where participants were asked about the impact of Covid-19 on multiple aspects of their lives, including mental health and wellbeing. Though there is no disaggregated data for ethnic minorities and the sample sizes were small, North East Scotland (including Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire) showed high levels of loneliness and anxiety, as well as low levels of happiness.

ONS research can be found online: Link.

Data Source: 2021: Community Planning Aberdeen. Link.

The Human Cost of Brexit (Health)

In an online roundtable discussion, members of community groups and third & public sector organisations reflected on Brexit’s impact on EU citizens in North East Scotland. Six speakers presented diverse perspectives and more than 65 people attended the discussion that followed, raising the concerns of local communities.

Participants referred to Brexit and Covid-19 as a ‘time bomb’ that would increase mental health problems among EU citizens.

Data Source: 2021: Shared Futures & No Recourse North East. Link.

Aberdeen City Health & Social Care Partnership (ACHSCP) and GREC, Survey & Focus groups

To help develop the new ACHSCHP Equality Outcomes, at the end of 2020 research was conducted with 192 people to better understand the health inequalities and challenges impacting people with protected characteristics in Aberdeen. For this, a survey was conducted, as well as discussion groups with community members with all (and sometimes overlapping) protected characteristics.

One of the key findings was that ethnic minority participants had lower rates of satisfaction with health and social care services than the average across participants from all demographics – 36%, compared with 48% on average. 25% were dissatisfied, compared with an average of 14%.

Ethnic minority participants also had slightly lower levels of positive responses to a series of health-related questions. For example, 57% felt they had a good experience with health and social care services, compared with 62% on average, and 27% reported a general good experience with some issues, compared with 18% on average. Only a third of ethnic minority participants felt they could “access the right health and social care services/support that best suited [their] needs,” compared with 40% on average, and a quarter disagreed with the statement, compared with 18% on average. Only one in five felt “informed, supported and involved as I need to be about my care,” compared with an average of double that, and a third disagreed, compared with 17% on average.

In the focus groups and other engagement activities, ethnic minority participants suggested that access to language support is required to improve access and delivery of health services, highlighting that language is one of the key barriers to feeling listened to when accessing these services. They also emphasised that in mental health services, one size does not fit all. Practitioners must be aware of cultural nuances and differences that can affect how mental health conditions are understood, evaluated and treated. This was a particular concern for African communities, especially in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, as it was acknowledged that more people would struggle with isolation but would feel uncomfortable speaking about it or seeking help.

The report also cited research conducted by ACVO in 2020, showing that current service provision in Aberdeen to address domestic abuse does not cater for the intersectional needs of people with disabilities, those from ethnic minority communities, LGBTQ+ communities, men and perpetrators.

Data Source: 2020: ACHSCP and GREC, internal documents.

Qualitative Data from Relevant Local Research (pre-2018)

Review of Local Research by SSAMIS and GREC (Health)

Focus groups and interviews in Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire (particularly Fraserburgh), conducted in a range of languages, suggest generally high levels of patient satisfaction with NHS services. GREC’s annual research for NHS Grampian shows increasing levels of satisfaction over the years, especially in Dental Services and Sexual Health Services, and satisfaction with Hospital Services, Community Nursing, Pharmacy and Ophthalmology Services being consistently high (sometimes very high). Overall, satisfaction levels with health care services are higher in Aberdeen than in Fraserburgh, most marked in GP services.

Many issues that migrants described in relation to healthcare can be attributed to the gap between expectations and reality, based on differences between healthcare in their countries of origin in Central and Eastern Europe. In particular, migrants often expressed frustration that they could not always refer themselves to specialists (e.g. for gynaecology, back problems), and many opted to use medical and dental services in their countries of origin for long-term health issues, and even some acute issues. There were also many complaints about the perceived ‘wait and see’ approach of GPs, who were reluctant to give antibiotics or further tests for minor ailments, and many participants felt there was not enough emphasis on preventative care. For example many participants were used to regular wellness checks with blood/urine tests in their countries of origin, whereas Scottish GPs tend to focus on suspected illnesses.

Generally speaking, migrants had very positive experiences of interpreting and of maternity care in the Aberdeen/shire context, and there was a real appreciation for certain aspects of Scottish healthcare, e.g. free prescriptions, medical devices such as hearing aids, etc. It was noted that some services were available through self-referral, such as optometry, that were subject to long waiting lists in other countries. Additionally, while there were complaints about waiting several weeks for a GP appointment, participants also discussed how on-the-day appointments in other countries were often subject to long waits.

Loneliness was a significant issue affecting migrants’ wellbeing, often stemming from being unable to establish local support networks due to language issues or working long hours. In Aberdeenshire, there were specific problems associated with working in the fishing and food production industries – for example, ongoing skin problems from working in cold, wet conditions in fish factories, breathing problems from working with specific types of seafood, etc.

Other research reports available on the GREC website: Link.

Data Source: 2017: SSAMIS: Migrants and Healthcare in Aberdeen/shire. Link.

New Scots (Syrian Refugees) in Aberdeenshire (Health)

In March 2018, 82% of the Syrian New Scots reported that their health had improved, either a little (65%) or a lot (17%). 12% of working-age adults were long-term sick or disabled. At the consultation event in September 2017, mental health was a key concern. Many participants mentioned significant problems with social isolation, separation from family members, the aftermath of trauma, anxiety about long-term immigration status, and the lack of Arabic-language mental health services. As with other issues, the language barrier made it difficult to access health services, and some participants had encountered health professionals who refused to use Language Line or request interpreters, instead referring patients back to the resettlement team. Another health-related issue highlighted in the consultation was poor availability of halal food in Inverurie and other parts of Aberdeenshire

Data Source: 2018: Syrian New Scots Partnership.

Summary & Priorities

There is limited quantitative evidence to understand health outcomes of ethnic minorities, as ethnicity is not consistently recorded by health services. Existing evidence suggests that Grampian’s poorest areas – in terms of health outcomes – are home to a higher proportion of ethnic minorities.

In terms of satisfaction with health and social care services, local research presents a mixed picture, showing high levels of satisfaction with NHS provision over the years, while also suggesting there is a gap when compared to the Scottish/British population. Lower levels of positive responses are also shown in a series of indicators compared to the Scottish/British population in relation to access to the appropriate health services and information. This reflects issues associated with language barriers and differences between how healthcare works in Scotland compared with other countries.

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic more people are experiencing mental health problems, and ethnic minorities are among the hardest hit groups. Evidence gathered both before and during the pandemic indicates that a ‘one size fits all’ approach in the provision of mental health services is problematic for ethnic minorities as cultural nuances might be underestimated.

Priorities

- Gain a better understanding of the particular health issues and outcomes of different ethnic groups in Grampian, including health inequalities arising from Covid-19.

- Address the disparate experiences of those accessing health services in across Grampian, targeting areas with high levels of social deprivation and ethnic minority communities.

- Increase understanding of the health system in Grampian, highlighting key differences with how things are done outside of the UK.