Please click each section heading for the full text of that section.

The consequences of pandemic-related disruption remain to be seen, but it is important to remember that many ethnic minority families face the interconnected challenges of low-wage or insecure employment, overcrowding, insecure tenancy, poverty, and digital exclusion.

Pupil Demographics

Ethnicity: Pupil Census Data

The annual pupil census records data for Scottish schools, providing more precise figures than the ONS population estimates, if only for children and young people. As shown below, schools in Aberdeenshire and Moray have smaller proportions of ethnic minority pupils than the Scottish average, while Aberdeen City has a much higher proportion. This makes sense, given that Aberdeen City has a large immigrant and ethnic minority population, and that 1/3 of babies born in Aberdeen City have foreign-born mothers.

Pupil Ethnicity, 2021

| Total Pupils | Scottish/ British | % | Total Ethnic Minorities | % | · | ‘White’ Ethnic Minorities | % | Other Ethnic Minorities | % | Not known/ disclosed | % | |

| Aberdeen City | 24260 | 16017 | 66% | 7902 | 33% | · | 3496 | 14% | 4406 | 18% | 341 | 1% |

| Aberdeenshire | 36647 | 32398 | 88% | 3973 | 11% | · | 2419 | 7% | 1554 | 4% | 276 | 1% |

| Moray | 12217 | 11063 | 91% | 1053 | 9% | · | 627 | 5% | 426 | 3% | 101 | 1% |

| Scotland | 704723 | 581846 | 83% | 108001 | 15% | · | 42975 | 6% | 65026 | 9% | 14876 | 2% |

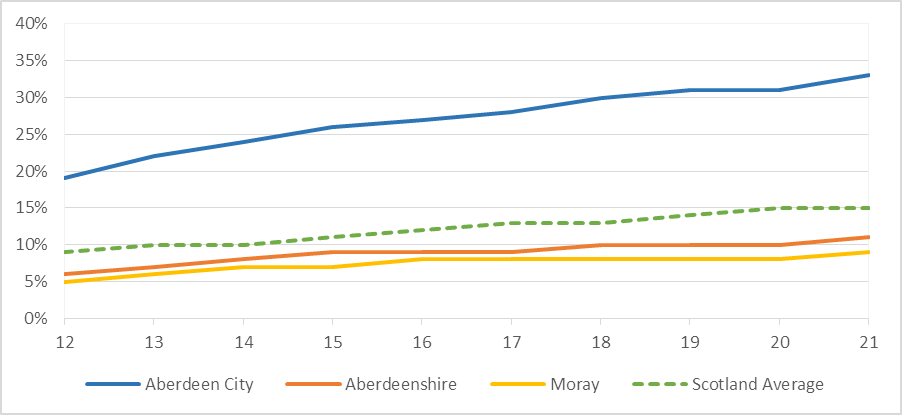

The proportion of ethnic minority pupils has been rising in the past decade, from 19% to 33% in Aberdeen City, 6% to 11% in Aberdeenshire, 5% to 9% in Moray, and 9% to 15% across Scotland as a whole.

Ethnic Minority Proportion of Pupils, 2012-2021

Data Source: 2021: Scottish Government Pupil Census, supplementary statistics (table 5.7). Link.

Positive Destinations & Qualifications

Attendance, Absence & Exclusion from School

In Aberdeen City in 2020-21, 33% of pupils were from an ethnic minority background. In Aberdeenshire the figure was 11%, in Moray it was 9%, and the Scottish average was 15%.

Attendance figures was broadly similar for ethnic minority and Scottish/British pupils, 90%+ in all areas of Grampian, and these were similar to other areas in Scotland. Apart from Gypsy/Travellers, there were no groups in Grampian whose attendance was below 88%.

| Scottish/ British | Gypsy/ Traveller | ‘White’ Ethnic Minorities | Mixed or Multiple | Asian | African, Caribbean or Black | Arab | Other | |

| Aberdeen City | 93% | 64% | 90-93% | 94% | 90-96% | 91-97% | 93% | 95% |

| Aberdeenshire | 94-95% | 67% | 94-96% | 96% | 90-97% | 91-97% | 93% | 95% |

| Moray | 94% | 65% | 93% | 94% | 88-97% | 95-96% | 96% | 93% |

In terms of exclusions from school, In 2020-21, ethnic minority pupils in Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire were under-represented: 14% of exclusions in Aberdeen City were of ethnic minority pupils, 10% in Aberdeenshire, and 9% across Scotland as a whole. In Moray, they were slightly over-represented, comprising 15% of exclusions.

Data Source: 2021: Scottish Government Pupil Census. Link.

School Leavers – Positive Destinations & Qualifications

Note: More recent data does not seem to be available for school leaver destinations by local authority and ethnicity. Below is the material from the 2018 edition of How Fair is North East Scotland?

The vast majority of school leavers in Grampian went on to positive destinations, including further education, higher education, training, employment and voluntary work. Ethnic minority school leavers in Grampian had slightly higher rates of positive destinations than their Scottish counterparts. The largest gap was in 2015-16, when 95.4% of ethnic minority school leavers went on to positive destinations, compared with 90.4% of Scottish school leavers.

Between 2013-14 and 2015-16, nearly all school leavers across Grampian achieved at least one qualification at SCQF Level 4 or better. At all levels, ethnic minority pupils achieved qualifications in higher proportions than their Scottish counterparts. For qualifications in level 6 or greater, Moray consistently had the lowest levels of attainment for all ethnic groups.

School Leavers’ Qualifications, 2013-14 to 2015-16

Percentage of pupils achieving at least one qualification at the SCQF level shown.

Ethnicity data was recorded as ‘white Scottish,’ ‘White non-Scottish’ and the other categories of non-‘white’ ethnicities.

| 2013-14: 4+ | 2013-14: 5+ | 2013-14: 6+ | 2014-15: 4+ | 2014-15: 5+ | 2014-15: 6+ | 2015-16: 4+ | 2015-16: 5+ | 2015-16: 6+ | |

| Aberdeen City – Scottish | 95.8 | 78.9 | 47.7 | 95.7 | 80.6 | 53.6 | 95.0 | 84.0 | 56.7 |

| Aberdeen City – Ethnic Minority | 99.8 | 91.5 | 76.0 | 97.3 | 91.2 | 78.9 | 99.3 | 95.5 | 78.8 |

| · | |||||||||

| Aberdeenshire – Scottish | 96.8 | 82.3 | 53.2 | 97.7 | 87.3 | 57.2 | 97.4 | 87.8 | 61.8 |

| Aberdeenshire – Ethnic Minority | 99.1 | 96.1 | 62.7 | 99.3 | 81.6 | 64.0 | 99.6 | 97.2 | 72.5 |

| · | |||||||||

| Moray – Scottish | 98.3 | 88.4 | 55.0 | 96.3 | 85.5 | 55.5 | 97.1 | 86.1 | 57.5 |

| Moray – Ethnic Minority | 99.4 | 95.6 | 63.2 | 98.4 | 89.9 | 65.5 | 98.6 | 92.7 | 60.7 |

Generally speaking, ‘White non-Scottish’ was both the largest ethnic minority group and the lowest-performing group among ethnic minorities, but this group typically performed better than their ‘White Scottish’ counterparts. In some other ethnic minority groups, 100% of pupils left school with at least 4, 5, or 6 qualifications. However, these tended to be small numbers of pupils (less than 20).

Data Source: 2016: Scottish Government, Attainment and Leavers’ Destination Data. Link.

Highest Level of Qualification

In the 2011 Census, ethnic minorities across Grampian consistently had higher levels of qualifications than their Scottish/British counterparts: 55.1% were educated to degree level or above, and only 10.6% had no qualifications. The figures for Scottish/British people were 26% and 24%, respectively. 80.1% of Africans (compare this to the relatively high unemployment rate) and 61.6% of Asians in Grampian were educated to degree level or above. In Scotland as a whole, 48% of ethnic minority people and 24.2% of Scottish/British people were educated to degree level or above, and 5.6% of ethnic minorities and 27.8% of Scottish/British people had no qualifications.

Data Source: 2011: Scotland’s Census, Table LC5202SC.

Qualitative Data from Relevant Local Research

The Human Cost of Brexit (Education)

In an online roundtable discussion, members of community groups and third & public sector organisations reflected on Brexit’s impact on EU citizens in North East Scotland. Six speakers presented diverse perspectives and more than 65 people attended the discussion that followed, raising the concerns of local communities.

In terms of education, speakers and participants mainly focused on Brexit’s impacts on higher education. Changes to University/College fees and funding will reduce the number of students able to afford the programmes they wish to pursue. Participants also discussed uncertainty in relation to future professional expectations, both for UK and EU students, and the latter group discussed not feeling welcome in the UK anymore.

Data Source: 2021: Shared Futures and No Recourse North East. Link.

Aberdeen Equality Outcomes Consultation (Education)

During August and September 2020, GREC conducted a survey to gather feedback from people with protected characteristics to feed into Aberdeen City Council (ACC)’s Equality Outcomes. The survey was complemented by a series of focus groups held in October and November. In total, over 200 people took part.

More education to prevent prejudice and discrimination was widely acknowledged as a necessity by research participants. In the survey, some participants explained that more training is needed to tackle day to day racism, which is sometimes not even acknowledged as such, while others highlighted that systemic discrimination must be addressed as well.

In the focus groups, a key theme was the desire to see more work around education and equality, particularly in schools. Ethnic minority participants said that schools should help promote inclusion and respect for diversity, for example celebrating festivals from different religions. Other participants also pointed to specific issues, such as halal meat not being provided by schools, which impacts children’s diets. This issue had been raised previously but with no suitable resolution.

Data Source: 2020: .

SSAMIS: Education

For migrants with children, schools were key considerations in deciding to settle in Scotland: they often expressed worries about uprooting children who were born in Scotland or who had moved with their parents at a young age. Scotland was seen to offer better long-term prospects for children who wanted to further their education or find good jobs. However, parents, relatives and carers had very mixed views of Scottish schooling. Initially some aspects of the Scottish education system could provoke criticism, as they differ greatly to systems in Central and Eastern Europe: e.g. less homework is given in Scotland, there is more emphasis on learning through play, less rote learning, etc – though some migrants liked the absence of corporal punishment. Pre-school/nursery education was perceived quite negatively, because there tended to be much less state provision in Scotland than in their countries of origin. However, opinions improved over time as migrants gained more experience and understanding of teaching in Aberdeen/shire.

Schools functioned as a key form of integration into the local community for children arriving in Aberdeen/shire. There were examples of younger children picking up English very quickly, even where their parents were struggling to find the time or resources to improve their own English. Parents also appreciated the extra help their children had been given help as new arrivals to local schools. Happily, there were few stories of migrant children being singled out by bullies for their nationality/race: younger children tended to be well assimilated at school. However, migrants who arrived as teenagers could have more difficulty fitting in.

Access to further/higher education was seen as a plus point for many migrants settling in Aberdeen/shire. A small number of participants had enrolled at Scottish universities since their arrival, and college courses in particular were very popular. Occupational mobility was significantly increased with language skills and/or Scottish qualifications, typically done part-time at local colleges. ESOL classes often served a wider role in integrating migrants, expanding their social networks and helping to familiarise them with Scottish life and local customs. Practicalities and the lack of transferability of existing qualifications meant that migrants often took courses in different subjects compared to their previous educational or work experience in Central and Eastern Europe. For example, migrants (particularly women) who had worked in professional roles would re-train or update their skills in hairdressing/beauty, cake decorating or accountancy in order to work more family-friendly hours or escape low-skilled employment.

Data Source: 2017: SSAMIS: Migrants and Education in Aberdeen/shire. Link.

Moray Council Anti-Bullying Survey

In autumn 2015, Moray Council conducted a survey among P4-S6 pupils and members of the public. 1974 pupils took part, representing 22% of the cohort. 3.9% of pupils said they had experienced bullying related to race or ethnicity.

Data Source: 2016: Moray Council, Moray Approach to Bullying in Schools. Link.

Summary & Priorities

While the consequences of pandemic-related disruption remain to be seen, quantitative evidence highlights that in terms of educational attainment, ethnic minorities in Grampian are routinely achieving higher than those from a Scottish/British background, with no relevant disparities in terms of school exclusions and attendance. This information is usefully compared to the economic/employment experiences of ethnic minorities, most notably Africans who have proportionally the highest level of attainment in terms of university degrees, but also the highest rate of unemployment.

The review of local evidence suggests that schools are one of the most important points of contact for newcomers’ integration. Parents’ engagement with the school community can be affected by language barriers and the pressures of working long hours and shifts, highlighting the importance of ESOL classes as a tool for improving integration through language learning.

The evidence also suggests that the older a pupil is when they arrive in Scotland, the more difficult it is for them to integrate into a new school, and those with high levels of English and qualifications gained in Scotland are more likely to be successful in the employment market. In line with the influence schools have in boosting integration, recent evidence shows that ethnic minority communities would like to see schools increasing the work they do around equality issues.

Priorities

- Making the most of the link between ESOL learning and integration opportunities.

- Ensuring that opportunities to learn English genuinely meet local needs.

- Getting a better understanding of the experience of ethnic minority young people starting school at a senior stage, and exploring what more could be done to support them.

- Getting a better understanding of how pandemic-related disruption has affected ethnic minority young people, especially those already disadvantaged due to poverty, digital exclusion or language barriers.

- Sharing best practice for communication between schools and families, especially identifying strategies to support families in meeting home-learning requirements, understanding the Scottish education system, etc.