Please click each section heading for the full text of that section.

1. Social bonds (connections within a community defined by, for example, ethnic, national or religious identity); 2. Social bridges (with members of other communities); and 3. Social links (with institutions, including local and central government services).

Ager & Strang, 2004, Indicators of Integration (PDF)

Social Attitudes Survey

The National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) carries out annual social attitude surveys across Scotland, with a sample of around 1500 people per question. While it is not possible to divide responses by region, there are some interesting points to note, covering Scotland as a whole. The most recent survey relevant to Social Connections was in 2015:

- A2.1 “People from outside Britain who come to live in Scotland make the country a better place.”

Since 2006, there has been a slight increase in the number of respondents who agree with this statement, and slight decrease in the number who disagree. - A2.3 “Scotland would begin to lose its identity if more people from Eastern Europe came to live in Scotland.”

38% of respondents agreed; 41% disagreed. - A2.4 “Scotland would begin to lose its identity if more black and Asian people came to live in Scotland.”

34% agreed; 33% disagreed. - A3.1 Feelings if a close relative married or formed a long term-relationship with someone who was:

Muslim: 49% happy; 20% unhappy.

Black/Asian: 62% happy; 5% unhappy.

Gypsy/Traveller: 37% happy; 32% unhappy. - “Have equal opportunities for Black and Asian people gone too far or not far enough?”

16% of respondents believed it had gone too far; 32% believed that it had not gone far enough.

Younger people and people with higher qualifications tended to answer the latter, while older people and those with lower qualifications were more inclined to answer the former.

Data Source: 2015, National Centre for Social Research. Link.

Key Missing Data

Much of the data that would help assess social bridges, bonds and links is simply not available. Data on the ethnicity of members does not appear to be collected by trade unions, political parties, voluntary organisations, etc. Local authorities do not consistently collect ethnicity data on councillors, council employees or service users. According to a Scotland-wide survey, the average councillor is a ‘white’ Scottish man, married, aged 50-59, “who is a well-educated homeowner from a managerial or professional occupation.” These results were similar to previous studies.

Qualitative Data from Relevant Local Research (2018-2021)

The Human Cost of Brexit (Social Connections)

In an online roundtable discussion, members of community groups and third & public sector organisations reflected on Brexit’s impact on EU citizens in North East Scotland. Six speakers presented diverse perspectives and more than 65 people attended the discussion that followed, raising the concerns of local communities.

Community members who attended the online roundtable event discussed how a sense of belonging was taken away during and after the Brexit campaign. They described how people in their communities stopped using their home languages outside, to prevent being targeted as ‘those migrants,’ which had a negative effect on their sense of belonging and feeling welcome.

Data Source: 2021: Shared Futures and No Recourse North East. Link.

Aberdeen Equality Outcomes Consultation (Social Connections)

During August and September 2020, GREC conducted a survey to gather feedback from people with protected characteristics to feed into Aberdeen City Council (ACC)’s Equality Outcomes. The survey was complemented by a series of focus groups held in October and November. In total, over 200 people took part.

More than two-thirds of ethnic minority participants felt that Aberdeen was welcoming, and more than half felt included in their local communities. Figures were similar for Scottish/British participants.

Around a quarter of all participants felt they had been excluded from cultural activities because of protected characteristics, and they were generally part of ethnic minority groups, including half of participants from African, Caribbean or Black backgrounds. The negative experiences they described in comments mentioned racism and being concerned due to previous attacks. A few participants were also targeted by racist comments at sports facilities, but around half of ethnic minority participants enjoyed exercising at a gym, sports centre or swimming pool.

Feedback from the focus groups highlighted that places of worship are key places to socialise for the African community, so their closure due to the Covid-19 pandemic disproportionally impacted this community’s sense of connectedness. Members of the Muslim community also discussed the impacts of the mosques being closed, but they spoke positively about the supportive nature of their local communities during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In broader terms, African participants identified a problem in the lack of representatives from their community in senior positions, both in the public and private sector, and during the development of new strategies and plans. European minority ethnic communities had mixed responses about feeling safe and welcomed in Aberdeen, with participants discussing positive experiences, but also challenges to access some services. To overcome these issues, participants suggested an increased focus on bringing people of different communities and cultures together, and an increased understanding of diversity to promote positive community relations.

Elphinstone Institute: Home-Hame-Дом-Dom

Home-Hame-Дом-Dom was a creative learning project, bringing people from different backgrounds together to build a sense of community and belonging in the North East. The project aimed to facilitate deeper engagement of Eastern European migrant communities and encourage meaningful integration with the indigenous populations, as social isolation and loneliness were identified as a considerable issue for parents and older migrants.

The evaluation report describes how activities and events, such as photography, sewing, and dance, helped participants from diverse cultural backgrounds increase their sense of connectedness and integration. In a follow-up survey both migrant and Scottish participants reported positive outcomes, including meeting new people, making new friends and professional contacts, learning new skills or developing existing ones, learning something new about other cultures, and improving language skills and confidence.

Building personal connections was very important to participants, especially as isolation increased during lockdowns, and connections tended to ‘ripple out’ into generating more connections. The project helped to improve integration and gave participants an opportunity to express their feelings, and also created moments of serendipity, when unexpected opportunities arose.

There were several relevant lessons learned through the implementation of this project:

- Translating the project documentation into the main community languages attracted a wider range of participants.

- Polish and Doric classes challenged English as the only important language for integration.

- Language skills developed informal methods – there are other options to learn a language besides a formal class, with images and videos key to making learning accessible.

- Learning through practical activities worked well to bring people together and integrate without focusing explicitly on language and integration. The creative nature of the activities helped to engage participants, shifting focus away from what might be perceived as threatening or embarrassing, and technology (e.g., translation apps) helped people to learn together.

- Spaces played a relevant role, as community centres did not attract migrants to participate. Acknowledging the need for flexibility, venues were identified that had meaning for participants, so they felt welcomed and safe.

- Fostering cultural democracy was important, along with making all activities as non-hierarchical as possible. All forms and expressions of culture were valued equally – including vernacular culture. Co-creation and process took priority over the ‘end product’ of the arts activities.

It should be noted that this is a summary of lessons learned – the full report includes more detail and examples.

Data Source: 2020: Elphinstone Institute: Home-Hame-Дом-Dom Final Report. Link.

Qualitative Data from Relevant Local Research (pre-2018)

Migrants’ Pathways and Journeys in Aberdeen

Focus groups were conducted to discuss migrants’ early experiences in Aberdeen, particularly around health related issues. For newcomers, a key source of information was word of mouth within their own ethnic or language communities, including friends, family, and even local restaurants with their national food. However, if local networks were not aware of services or resources, a newcomer could miss out on the help they needed. It could also be difficult to find others who spoke the same language. Popular points of contact with institutions included GPs, the local council, and schools, colleges or universities. Some participants also turned to landlords, dentists, local charities, religious groups, community centres and groups linked to their country of origin.

Data Source: 2017: GREC. Link.

GREC Research (Social Connections)

The following research is summarised below:

- ‘Life in Aberdeen’ and ‘Life in Aberdeenshire’ Surveys, 2018

- Tackling Economic Barriers pilot study, 2017

- ‘Creating a Fairer and More Equal Aberdeen,’ 2016-17

351 people took part in the 2018 research, of whom 105 were ethnic minorities (29.6%), including several who completed the surveys in Polish. 197 participants were Scottish, English or British, 29 participants skipped the question on ethnicity, while 19 identified themselves only as ‘white’. 65 people took part in the 2017 pilot survey, which was targeted at ethnic minorities, and only one participant was Scottish. For the 2016-17 research, 225 people took part in a survey in the second half of 2016, mostly at ten community engagement events with groups representing seven of the equalities characteristics (race/ethnicity, religion/belief, age, disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender reassignment). 120 participants were Scottish or British, 84 were ethnic minorities, and 18 did not provide a useable answer.

Opinions of Aberdeen/shire

In the 2018 research, 81.9% of ethnic minority participants felt that Aberdeen or Aberdeenshire was a welcoming place, and 70.5% felt part of their communities. The figures for Scottish/British participants were 66.5% and 58.4%.

There were similar findings in the 2016-17 research: just over half of both Scottish/British and ethnic minority participants said they were active in their local communities, and around 90% said they feel able to participate in public life. 76.9% of ethnic minority participants felt that equality and diversity are welcomed and celebrated in Aberdeen, compared with 63.6% of Scottish/British participants.

In the 2017 pilot study, 83.1% of participants agreed that their neighbourhoods were welcoming places, 78.5% felt part of the communities where they lived, and 56.9% said they were active in their local communities.

Relations Between Groups

In the 2018 research, around three-quarters of Scottish/British participants felt that ethnic minorities are treated with respect, while a third of those from ethnic minority backgrounds disagreed with this statement. Three-quarters of both Scottish/British and ethnic minority participants agreed that people from different nationalities get along well in their local area.

In the 2016-17 research, 46% of Scottish/British participants and 55.4% of ethnic minority participants felt there are good relations between communities. Feedback urged Aberdeen City Council to organise more multicultural events, along with events highlighting the cultures and experiences of migrants, to further improve relations.

Use of Local Facilities

In the 2016-17 research, 60.3% of Scottish/British participants and 70.8% of ethnic minority participants said they used the city’s cultural and sporting facilities. In 2018, the frequency of using some community facilities was similar between Scottish/British and ethnic minority participants; nearly all used local shops and a health centre or GP, three quarters used local parks, and around half used a gym or swimming pool. Ethnic minorities made more use of libraries (64% versus 39%), schools or nurseries (54% versus 27%), community centres (53% versus 35%), places of worship or religion (30% versus 16%), and advice services (13% versus 8%). Scottish/British people were more likely to use local pubs or restaurants (82% versus 57%), and slightly more likely to use buses (75% versus 67%). For both groups, those who felt part of their communities tended to use more community facilities.

Involvement in Local Groups

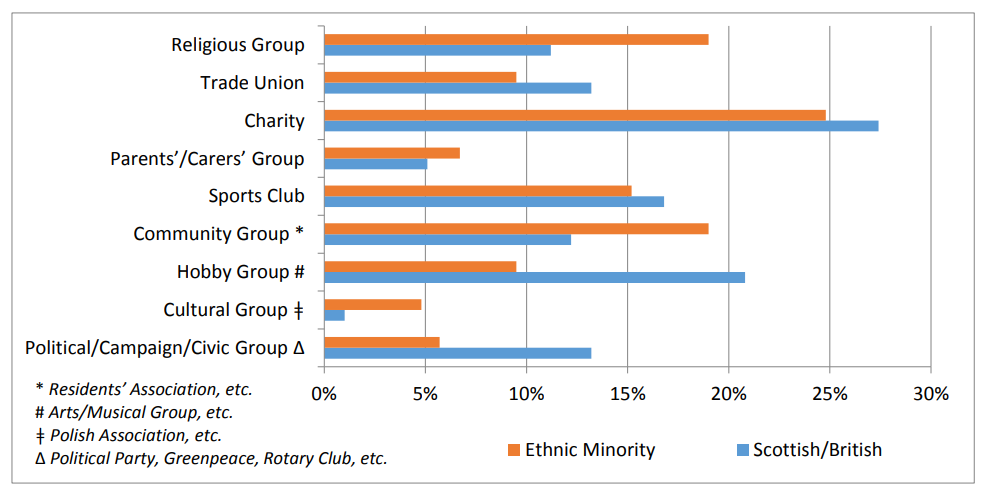

There were similar levels of involvement in local groups between ethnic minority and Scottish/British participants – just under 70% were involved in at least one group. As shown in the chart below, charities were the top groups, followed by religious, community and sport groups for ethnic minorities, and hobby and sport groups, political/campaign/civic groups, and trade unions for Scottish/British participants.

Involvement in Local Groups in Aberdeen/shire, by Ethnicity

Friendships

As with other areas, there were similar patterns between ethnic minority and Scottish/British participants here. In the 2018 research, the largest proportion of both groups met their friends at work – two-thirds for ethnic minorities, and nearly 80% for Scottish/British participants. Around half of both groups found friends at school, college or university, or through other friends, or through their children or other family members. Around 30% of both groups were friends with their neighbours, and around 10% met friends online. Half of Scottish/British participants met their friends through hobbies, sports, cultural groups, pets, or other types of groups, and this was the case for a third of ethnic minority participants. 19% of ethnic minority participants met their friends through religious groups, compared with 7.6% of Scottish/British participants.

A large majority of both ethnic minority and Scottish/British participants had friends who were different nationalities – 89.5% and 80.2%, respectively. A slightly smaller proportion had friends who spoke a different first language: 87.6% and 71.1%. In the 2017 pilot study, 84.6% of participants had friends of many nationalities, and 80% said their friends included Scottish people. Unsurprisingly, participants who felt part of their communities were more likely to have diverse friendships.

Data Source: 2018: GREC. Link.

Summary & Priorities

It is difficult to find existing data to build a clear picture of the social bridges, bonds and links that support integration across diverse communities. Most of the evidence that we have comes from four community surveys, the most recent undertaken in 2020 . On the whole, the results of the surveys are positive as they consistently show a high proportion of ethnic minorities that felt that Aberdeen or North East Scotland is a welcoming place, and who feel they are part of their local communities. However, for these two indicators there was a decrease in the positive responses between 2017 and 2020 – not noted in the Scottish/British population – which may relate to the implementation of Brexit, as suggested by qualitative evidence.

Findings from 2016-18 surveys suggest that a high proportion of both ethnic minorities and Scottish/British participants are involved in community groups and have friendships across ethnic and language groups. The detrimental effect of Covid-19 in these and other indicators of social connectedness were highlighted by members of ethnic minorities, especially by those involved with faith communities. Considering this alongside the findings in other sections, more research is necessary to look into the experiences and feelings of people (from both ethnic minority and Scottish/British communities), in order to better understand the consequences of the pandemic and Brexit, especially in regeneration areas.

Priorities

- Gaining a greater understanding of social bonds, bridges and links within regeneration areas in Grampian.